Two Luso-Africans, two former deputies, and two positions that are diametrically opposed. Joacine Katar Moreira, a historian and former parliamentarian for the party Livre, and Hélder Amaral, a lawyer and former CDS deputy, discuss their reactions to the President of the Republic’s speech on April 25 on Portugal Pulse.

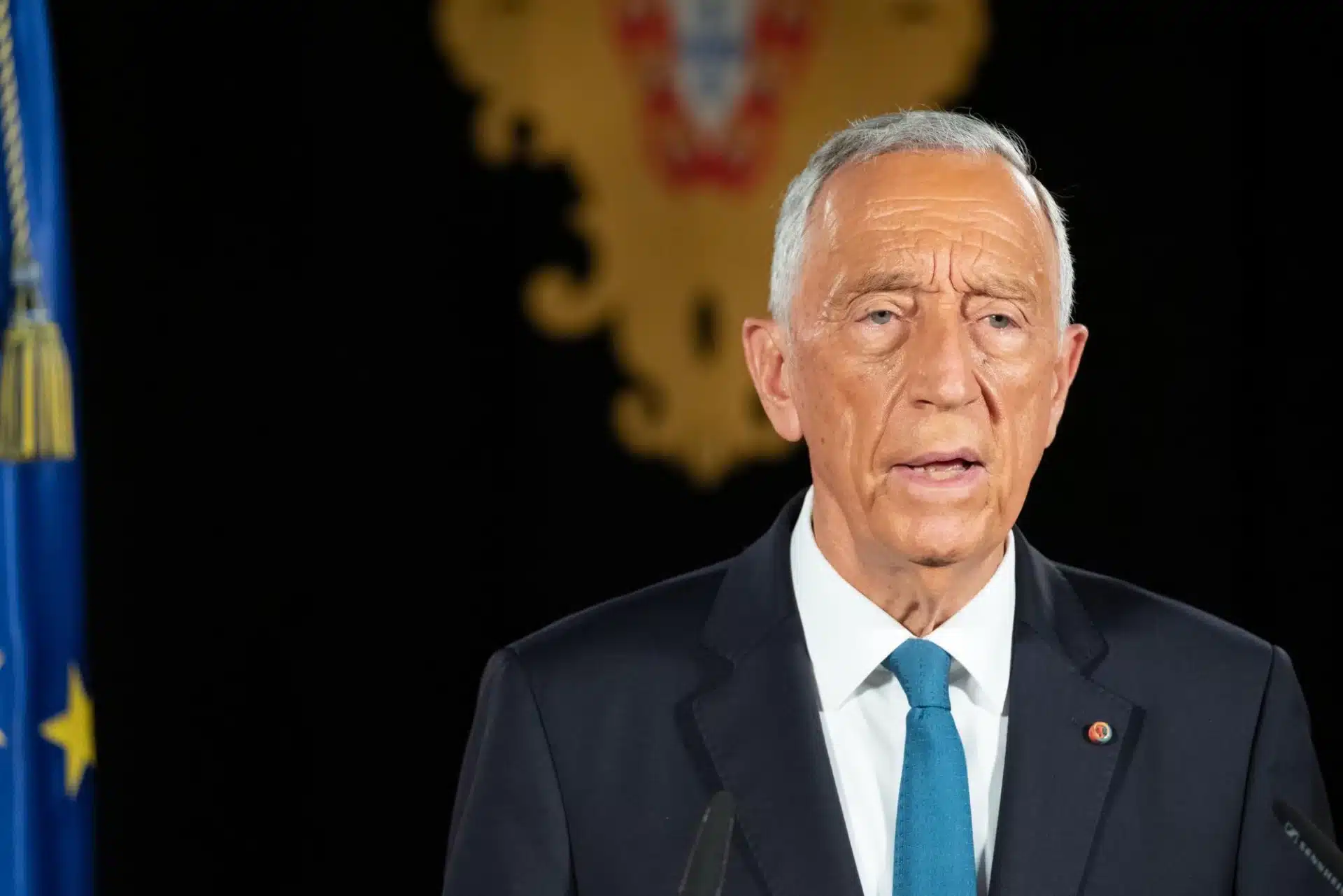

Never before had a representative of the Portuguese state taken such a position: the President of the Republic argued that Portugal owes an apology for its colonial past and must accept full responsibility for the exploitation and slavery that occurred during this time. Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa’s rare statement on a contentious and deeply divisive issue in Portuguese society was made in Parliament, in the middle of his 25th of April speech: “It’s not just saying sorry – due, no doubt – for what we did, because sometimes apologizing is the easiest thing to do; you apologize, turn your back, and the job is done. “Rather, it is about accepting responsibility for the consequences of our past actions, both good and bad,” he emphasized.

The intervention was made before Lula da Silva, the president of Brazil, i.e., before the head of state of a territory that was colonized and exploited by the Portuguese for centuries. Thus, it appears that Marcelo has opened the door to a formal apology, which other European nations, including France, the United Kingdom, and most recently the Netherlands, have already issued. Six million Africans were reportedly kidnapped and forcibly transported on Portuguese ships to be sold on the African continent between the 15th and 19th centuries.

So far, some kind of apology about the colonial past has only been heard from the Prime Minister, António Costa, and in relation to a very specific event: the Wiriamu massacre, which took place in December 1972, in Mozambique. This massacre, revealed by the British press in 1973, was for many years ignored in Portugal. António Costa’s statements came in September, during a visit to Maputo, during which the socialist classified the massacre as an “inexcusable act that dishonors” Portugal’s history. “In this year of 2022, almost 50 years after that terrible day of December 16, 1972, I cannot fail to evoke and bow before the memory of the victims of the Wiriyamu massacre, an inexcusable act that dishonors our history,” he said.

In Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa’s case, the President had stated, in December, also regarding the 50 years of the Wiriamu massacre, that it is time to assume “in full what was the unacceptable and terrible work of some”, but held Portugal responsible as a whole. The acknowledgement was released in a note published on the Presidency website with the title “It is time for us to assume Wiriyamu.” Years earlier, in 2018, during a visit to São Tomé, the head of state had already referred to the Batepá massacre, which occurred 70 years ago: “Portugal assumes its history in what it has of good and bad, and assumes namely, at this moment and in this memorial, what was the sacrifice of life and the disrespect of the dignity of people and communities,” he said.

In fact, Marcelo’s words had never been more emphatic than on this April 25th: “To apologize – due, no doubt – for what we did.

“It is never too late to ask for forgiveness”

According to Joacine Katar Moreira, a Luso-Guinean historian and former member of the Livre party, “it is never too late to ask for forgiveness, even if it is too late to be forgiven. The activist, who as a legislator always attempted to place this issue on the political agenda, believes that “the President does well to remind the nation of Portugal’s historical obligation.”

The former representative hopes that these statements demonstrate a “progressive awareness of the significance of Portugal accepting and assuming its imperial history and the violence that accompanied it.” She affirms, however, that “it would be important” that the head of state “does not give one for the carnation and another for the horseshoe, when in the same speech he speaks of ‘national design’ and of Portugal having been a ‘platform between oceans, cultures, and peoples’ during the colonial era, omitting its implications and effects on the colonized countries and peoples.

Joacine Katar Moreira emphasizes that “the President has a confused and diffuse discourse when it comes to the Portuguese colonial period and decolonization” and that, since his election, “he has made absolutely nostalgic and Lusotropicalist statements, which reinforce a vision of the colonial empire that contrasts with portions of his statements on April 25.”

He allowed himself to be “carried away” by others.

Former CDS deputy Hélder Amaral admits to Portugal Pulse that “that portion of the speech” surprised him. The centrist believes the president “caved in” to the media and “acted like the youngest man in the room.” Amaral, a Luso-African born in Angola, believes that apologizing for the colonial past “brings neither a solution nor a positive contribution to the structural racism that exists in Portugal.”

The attorney emphasizes that “the country’s history was what it was” and “has both good and bad aspects,” but that apologizing “is neither necessary nor useful.” “I don’t believe the question even exists; I don’t know if any of the former colonies have ever filed for compensation, but I doubt it. “I don’t know if any former colonies have raised this issue, and I don’t believe they have,” he continues. Amaral continues, “And where does this end, with the first dynasty? Where does it stop? Did we all begin to apologize for historical errors? Where does it begin and where does it end? Or is it merely a response to the questions posed by the current revisionist movement and by those in society who decide to raise irrelevant questions?”

On the other hand, the former representative questions “what sense it makes” to apologize for the colonial past “when we continue to discriminate against people from Angola, Mozambique, and So Tomé?”Perhaps it would be preferable to apologize for structural racism rather than for the events of the twentieth century.

“Yes, I will be marked; the colonial war and decolonization have marked my skin, and I will be marked for the rest of my life. But these are one’s circumstances; one must know and comprehend the past before moving on. As I’ve previously stated, he emphasizes, “maybe correct, maybe change your attitude, maybe view the former colonies differently.”