The Orthodox community was one of the fastest growing in Portugal in recent decades, growing from 2,564 people in 1981 to 60,381 in 2021, while the Muslim community grew from 4,335 residents in the country to 36,480, according to INE data.

Lusa compared the results of the general census of the resident population in 1981 with those of the most recent Census (2021) to understand the evolution of religious freedom in democratic Portugal. In the pre-1974 Census (1970), the question of religious plurality was not asked.

According to the data available for 1981, the Protestant religion included 39,122 people, with 59,985 responses in the “other Christian” category. In 2021, the National Statistics Institute (INE) counted 186,832 Protestant/Evangelical churchgoers, 63,609 Jehovah’s Witnesses and 90,948 citizens belonging to another Christian religion.

The Jewish community grew from 5,493 in 1981 to 2,910 in 2021, taking into account the country’s resident population (aged 12 and over in 1981 and 15 and over in the most recent census).

A total of 6,721,889 inhabitants responded to the 1981 survey, of whom 6,352,705 identified themselves as Catholics. In the latest census, out of 8,781,900 respondents, 7,043,016 said they were Catholic.

In 2021, there were already 19,471 Hindus and 16,757 Buddhists (no comparison with 1981), while people who identified with another non-Christian religion amounted to a total of 24,366. Around 1.2 million had no religion, compared to 253,786 at the start of the 80s.

The world’s great religions have always been present in Portugal, albeit without rights and sometimes subject to persecution, as was the case with the Jews and later with those who opposed the colonial war and refused to do compulsory military service, such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

In an interview with the Lusa news agency, the president of the Religious Freedom Commission, Vera Jardim, recalled that before April 25, many Spanish, Anglican, English, American, Lutheran and other religious orders were expelled from the colonies, as were Catholics in favor of the independence of the overseas territories.

“There was persecution of minority churches before April 25, especially in connection with the colonial war, because many members of non-Catholic churches and even some members of the Catholic Church had spoken out and were against the colonial war,” he said.

Although they were allowed, the minority churches didn’t have “a minimum legal status”, with rights and duties: “There were several religions. In fact, there are religions that have been in Portugal for 200 years and more,” he said.

“The Baptists, the Lutherans, the Jews, we had the expulsion of the Jews from the start, but then they had complete freedom of worship. All these religions had their role in Portugal and were even well established in some Portuguese colonies. They had missions. There were the Catholic missions, which in fact were entrusted by the state with teaching, teaching practically, with the exception of a few high schools in the capitals of Angola, Mozambique, etc. the rest was in the hands of religious organizations of the Catholic Church and some non-Catholic missions and these non-Catholic missions, in general, were accused by the regime and some expelled,” exemplified the former Minister of Justice, who was committed to regulating religious freedom.

Vera Jardim also mentioned the Jehovah’s Witnesses. “They were persecuted by the so-called Estado Novo because they refused to do military service. There were, in fact, lawsuits against several members of the Jehovah’s Witnesses, who were a minority religion and still are, still exist,” she stressed.

Portugal has always lived with the cultural heritage of the world’s great religions, both Christian and non-Christian, with a strong Islamic presence, especially in Mozambique and Guinea.

“There were small Jewish colonies that had been formed since the Republic and at the end of the monarchy. Until the Republic there was an official state religion and only foreigners could have other religions, the Portuguese couldn’t have other religions,” he recalled.

The English and German colonies formed small religious groups representing the various Protestant churches.

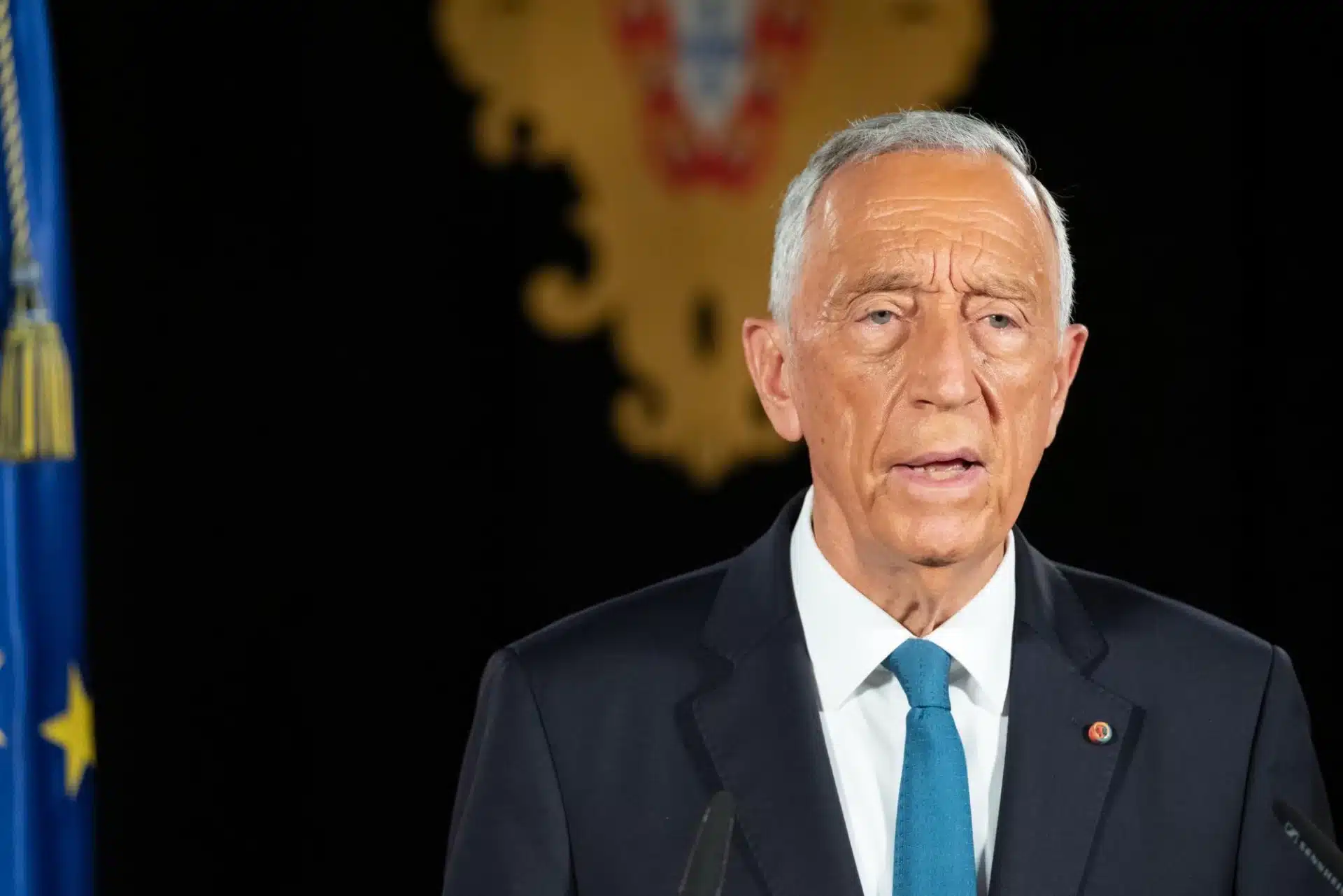

“It was only Marcello Caetano, in 1971, who, during the so-called Caetanist opening, passed a law on religious freedom. Yes, but it obliged religions to register, obviously, in order to have certain rights, as exists today, but no religion managed to register. The law was made in such a way that none of the religions established in Portugal, the Seventh Day Adventists, for example, a well-known Protestant religion with a worldwide reputation, tried, the Baptists too, but they didn’t succeed. There were small religious groups, but they didn’t manage to obtain a minimum legal status and that’s what the religious freedom law of 2001 did,” he concluded.

For Vera Jardim, the existing law has responded and is considered to be one of the most liberal in Europe, although there are aspects to be improved when it comes to applying the legislation in closed environments, such as prisons and even in hospitals and the Armed Forces.

Although he believes there is no need to revise the law, given the growth of new communities, the president of the Commission has warned of the need for greater sensitivity to the support that must be given to those who are religious, whether they are in prison, in a hospital or serving in the Armed Forces.

“There are special laws for these situations and these laws were passed and published precisely because of the religious freedom law. And there are flaws there, there continue to be flaws,” he admitted.