Director and producer Nelson Ponta-Garça has just published a book about the Portuguese presence in Hawaii and says that this may be the future of other communities in the United States.

When Portuguese-Americans Nelson Ponta-Garça and Danny Abreu were working on a project about the Portuguese presence in Hawaii, they had a running bet between them: how many people they asked at random would have Portuguese ancestry? “Almost one in two had a Portuguese rib,” Nelson Ponta-Garça tells DN. “From the singer in the restaurant to the person driving the shuttle to the bartender or the restaurant owner. More than half had a Portuguese rib,” he recalls. “I think it’s a fantastic thing.”

The director and producer spent years working on this project, which began as a documentary and has now been turned into a book. Portuguese In Hawaii: The History of Generations documents the long history of Portuguese emigration to this archipelago, which began in 1878, mainly from Madeira and the Azores.

“It’s a fascinating story of emigration,” describes Nelson Ponta-Garça, who included in the book more than 50 stories and interviews with players from the four main islands where there are Portuguese people, Oahu, Maui, Kauai, and the Big Island.

“More than those who made it to mayors of Maui or Kauai or business people who mastered their fields, I would highlight the stories that people still remember their parents’ trip, their grandparents’, great-grandparents’,” explains Ponta-Garça. “Trips of four, five, six months by boat, where half the people who came on the trip died and with children being born on board.”

The first record of a Portuguese emigrant to the islands dates back to 1814, according to the Library of Congress; his name was João (John) Elliott de Castro and he worked as a physician for King Kamehameha.

But most of the Portuguese who went to Hawaii went to work on sugar cane plantations and arrived between 1878 and 1913, to an archipelago that was still an independent nation.

“This whole epic is one of the reasons why I wanted to do this book, to leave this record and so that these stories will not be forgotten,” points out Ponta-Garça.

The risk of forgetting is always real in emigrant communities, but even more so in a geographically isolated region where communities have not maintained strong ties to their language and country of origin.

“One of the things I usually say, without being alarmist, is that if we go to Hawaii we can see what the Portuguese community in California will be like in thirty or forty years,” stresses Nelson Ponta-Garça. “We mainly find people whose grandparents and mostly great-grandparents were from Portugal, people who have an affinity but not all of whom are sure where they came from,” he says. “Many are not even sure where they are from anymore. They never came back.”

It is estimated that about 10% of Hawaii’s population, which totals 1.442 million people, is of Portuguese origin. In the past there had already been works focusing on the Luso-Hawaiian community, but not recently. According to Ponta-Garça, there hasn’t been an updated publication with local players in this format for a hundred years. And this also reflects the weakening of ties to Portuguese identity.

“What you see that’s different is that it’s a much older community and in essence it’s a mirror of what the California and New England community will be as well,” the author considers. “Although Hawaii is much more isolated geographically and has other constraints, what happened there I think will happen in the other communities. It’s almost traveling into the future.”

Ponta-Garça has close knowledge of these realities because he has been documenting the communities for over ten years and created the Portuguese In series. The work began with the documentary Portuguese in California, in 2014, followed by the publication of a book with the same title. As the state with the highest concentration of people of Portuguese origin, almost 350,000, California has communities that maintain a strong connection to their Portuguese identity.

This was followed by Portuguese in New England, in 2016, with a focus on the whaling industry and ten generations of Portuguese in this eastern region of the United States, where the identity connection is strong.

But in Hawaii, the distance and the seniority of the emigration weakened the ties.

“You notice a community almost at the end of its journey,” says the author, aware of the importance that his work can have. “I think that both the documentary and the book came to give some dynamism here. We did events on several islands and tried to mobilize and meet the most interesting organizations.”

The events to present the book on several islands were always attended by the Consul General of Portugal in San Francisco, Pedro Pinto, who has been working constantly to promote the community in the United States.

In Oahu, the presentation took place at the city hall, which has a long history with Portuguese mayors and councilmen, organized by honorary consul Tyler dos Santos-Tam, who is also of Portuguese descent.

On the other islands, the events took place in Portuguese chambers of commerce, historic centers, cafes, and physical locations with links to gastronomy and the ukulele, the musical instrument based on the ukulele.

The tour with the presence of the consul “ended up having an impact of making the community more dynamic, motivating them to stay connected, and awakening them to Portugal and their roots,” considers Ponta-Garça. This was important because “everything is dormant,” he says. “Even community organizations with leadership from older people who have made a big contribution but are already tired and some are even discouraged by the volunteer life and what it entails.”

Hints of portugality

In McDonald’s Hawaiian restaurants, there is a unique menu item that alludes to the Portuguese influence on the archipelago’s cuisine: Portuguese sausages. Elsewhere one finds “pãó dôcé” and malassadas, commonly written as “malasadas.” Leonard’s Bakery in Honululu always has lines out the door with customers wanting to get the malassadas, described as “Portuguese doughnuts.” There are local politicians with last names like Cravalho, Victorino and Tavares.

On Oahu, Nelson Ponta-Garça says he witnessed “the shortest and fastest procession of the Holy Spirit in the whole world,” near the famous Waikiki beach. The processions of the Holy Spirit are an indelible mark of the community in the United States, attracting thousands of Portuguese-Americans in a demonstration of both faith and Portugueseness.

There are streets with familiar names, like “Machado,” “Lusitana,” and “Madeira,” and whoever goes up gets to the Punchbowl area, where besides having a large Portuguese community there is a chapel, the Punchbowl Holy Spirit. It is the only physical place on the island of Oahu where there is a Portuguese space and where the Festa is celebrated, which they call “Dominga.”

On the Big Island, which once had 50% of its population of Portuguese origin, is where you can find the most evidence of Portuguese emigration. The historic center portrays the history of sugar cane, where the Portuguese were relevant, and the chamber of commerce has a project to make one of the largest Portuguese community centers in America, which encompasses everything from music, dance and the Portuguese language. This cultural aspect is important, reflects Ponta-Garça. “Hawaiians are very aware that the ukulele is a Portuguese instrument, brought by Portuguese people who taught the king to play.”

Signs of Hope

The dilution of Portuguese communities in Hawaii can be countered with signs of hope and closeness that have become more visible in recent years. The documentary and the book have helped mobilize associations and there is a renewed attraction to Portugal, whose profile in the United States has reached an unprecedented peak.

“A lot of positive things are happening and there is some more connection going on,” the author stresses.

“I know many people who had never been to Portugal or had been many years ago and have come in the meantime,” he continues. “Many who talked about coming in interviews are making arrangements to do so this year or next year.”

There are not only more visits and trips planned, but also a partnership project: the creation of several sister cities between Hawaii and Madeira and the Azores is being worked on. “There is also talk of a connection between Nazaré and Hawaii because of the issue of the two biggest waves.”

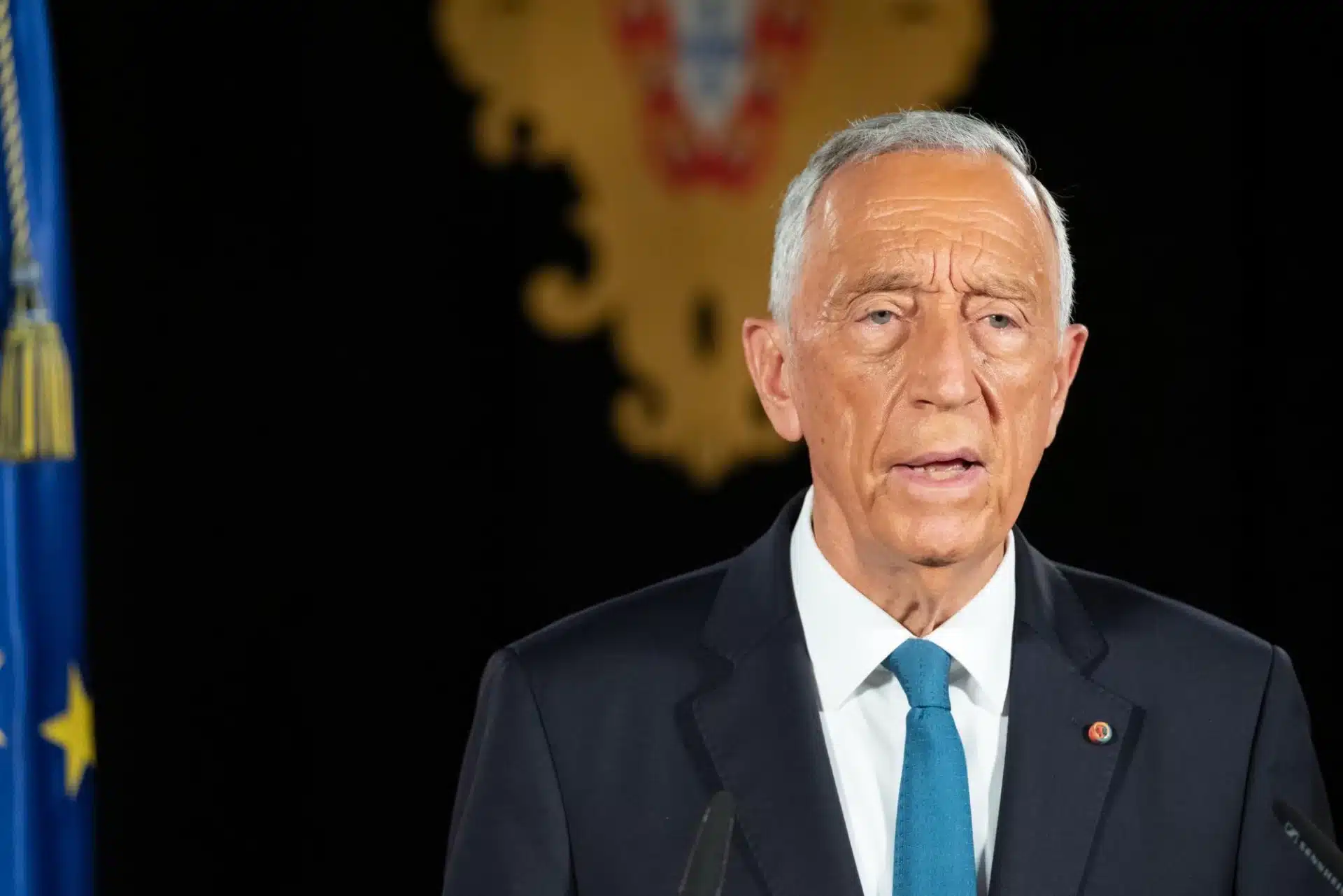

These types of private initiatives are essential because there are rarely official events and connections that cross over to Hawaii. When he was in California in September 2022, President of the Republic Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa received a ukulele from Honorary Consul Tyler dos Santos-Tam and expressed a desire to visit a community that is “antique, antique, one of the oldest and most resilient that lives there in isolation, even more so at the end of the world.”

But justifying the displacement is complicated, the president admitted, especially at a time of economic contraction.

Nelson Ponta-Garça alluded to this. “Politically it’s difficult for a secretary of state, a regional government president, a minister or even the President of the Republic to justify a trip to Hawaii,” he says. “There is the perspective of the general population that it’s a waste of taxpayers’ money,” he continues, to go to a paradisiacal place with postcard beaches. “It becomes difficult to justify these trips, and what happens is that there is rarely a political presence or an exchange presence,” the author stresses. “There are few or none.” That’s why the book tour with consul Pedro Pinto and the agreements for sister cities take on so much importance right now.

Meanwhile, the documentary is available for viewing on the PortugueseIn.com website and the book can be bought by anyone in the United States. It is also available in some libraries of institutions in Portugal, such as that of the Presidency of the Republic, and has been given to secretaries of state and ministers. “This is a record of this community,” stresses Ponta-Garça. For future generations to remember, even if they never learn Portuguese again.